MY VIEW BY DON SORCHYCH | SEPTEMBER 28, 2011

R.B. Patterson III

My first job after college in 1960 was with Radiation Inc. in Palm Bay, Florida near Melbourne. Radiation was a small company, perhaps with annual revenue of $25 million.

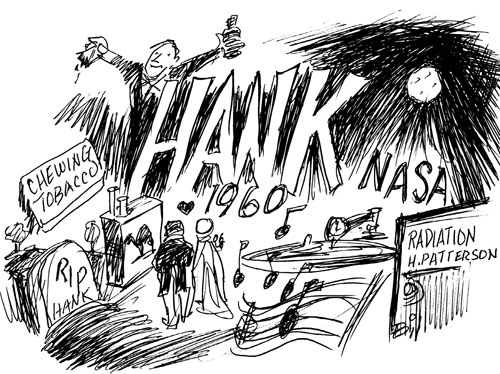

Radiation’s expertise was telemetry. I was assigned as a circuit designer on a struggling and money-losing telemetry system for Northrop, Inc. I was put in an office with “Hank” Patterson, officially Raymond Braxton Patterson and sometimes R.B. Patterson, III.

This was the first year Radiation had recruited Big Ten schools. It had only recruited in southern schools up to that point. As a consequence, all the employees were either southern citizens or graduates from schools south of the Mason Dixon Line.

The communities were also segregated. There were black and white drinking fountains, and white movies and restaurants.

I was viewed with suspicion as a Yankee, even though I was apolitical in those days. I have written about some of those “Yankee experiences” in the past.

Hank was single in those days and a partier of note. He would show up late and wash his face in the drinking fountain to sober up. Then he would come into our office, stretch, yawn and unfold a long plastic strip from a laundry bag to reveal a plug of chewing tobacco. He would bite off a chunk of tobacco, shove it inside his cheek and sit down. Then he would pull a pack of Camels from his shirt pocket and light up.

In those days, slide rules were the tool used by engineers; computers came way later. Hank worked all morning on designs while chain smoking. When lunch time came, he would throw the cud of tobacco in the waste basket and go to the company cafeteria.

He returned, repeating his earlier ritual, smoking and chewing until quitting time which was often late.

After about a week of this, my curiosity was overwhelming. I said, “Hank, every morning and after lunch you put chew in your mouth, yet you don’t have a spittoon. Where do you spit?” Hank replied, “Gentlemen don’t spit. I swaller it.”

Hank said he needed “connections” to be employed by Radiation because he was a C and D student at the University of Florida. He said he attended college to learn to be an engineer and hadn’t cared about grades. He was an incredibly competent engineer who was often visited by other engineers to break through bottlenecks.

Hank was a virtual encyclopedia across a wide range of disciplines.

After about three years of designing circuits I was put in charge of an airborne telemetry design group which included Hank. As usual he was the czar of circuit design along with another devoted southerner, Bill Eddins.

We designed telemetry systems for aircraft, missiles and the NASA moon landing system, including the Lunar Excursion Module.

Joe Boyd was hired as the President of Radiation and his fondness of PhDs led him to try them in senior management positions.

My group had a lot of camaraderie and I had frequent house parties. In one of a newly hired director’s first appearance at a party he said, “Ahh the Brandenburg Concerto,” commenting on the background music in the room. Hank, who was the center of attraction with a group of engineers said, “Ahem, that is Beethoven’s Fifth.” And Hank was right. The newly minted director left early.

When Hank was about 32 he invited me to his wedding. Arriving at the chapel I couldn’t find any woman in a gown that wasn’t about as old as Hank’s mother. When the bride and groom held hands I realized his new bride could have been his mother. What do you do in a situation like this? Nothing.

Hank later said he recognized that people thought he had a mother fixation. He said he didn’t care. He and Cleo loved each other and that was all that mattered.

Cleo owned an accounting company and was really bright. She took over Hank’s life in a good way. For one thing, she bought clothes and dressed him. She was proud he didn’t look like the Hank of old who dressed and walked like a plowboy.

Later, I transferred to the Microelectronic Division and asked Hank to transfer. I got a call from Cleo who asked a barrage of questions to assure the transfer was in Hank’s best interest.

She often called before our monthly communication meetings to be sure Hank left home with jacket and tie on that day.

Hank was in demand and his reputation grew over the years. He once visited a splinter off Radiation in Fort Lauderdale. One of the half-dozen founders asked how Cleo was. Hank said she was fine and awaited him in the car.

The founder said for God’s sake it is July and boiling out there – bring her in. She came in wearing short shorts, her bustiness preceding her. She fumbled in her cleavage, pulled out a soggy pack of camels, put one between her lips, leaned across the conference table and said “Light me.” Everyone’s eyes went to the corner of the room.

Hank grew up in Thomasville, Ga. and had endless stories about the politicians, law enforcement people, deacons and just plain folks. His renditions drew crowds wherever he went.

Both he and Cleo were fond of beer and Hank told me about a home project where he installed kegs of beer and piped it into all the home’s rooms.

Harris Corporation bought Radiation in 1967 and I left in 1979. I returned to the area in 1981 and once again invited Hank to join me, this time in a start up. I got the expected call from Cleo and he joined me again.

I left in 1985, moved to Arizona and lost track of them, during which time Cleo must have passed away. Apparently Hank then married a woman named Melva Lee and was married to her for 23 years. I received an obituary from my friend Al Nash. The obit included a color photo of Hank in a suit and tie. I sent it to Shirley Meckley, my secretary at Radiation, who said she never knew him to dress that way. His attire was either his Cleo’s enduring mark on Hank or an old family photo.

R.I.P. my dear friend.