AUGUST 11, 2011

Blue Fridays

Very soon, you will see a great many people wearing blue every Friday. The reason? Americans who support our troops used to be called the 'silent majority.' We are no longer silent, and are voicing our love for God, country and home in record breaking numbers. We are not organized, boisterous or overbearing.

Many Americans, like you, me and all our friends, simply want to recognize that the vast majority of America supports our troops. Our idea of showing solidarity and support for our troops with dignity and respect starts this Friday -- and continues each and every Friday until the troops all come home, sending a deafening message that every red-blooded American who supports our men and women afar, will wear something blue. By word of mouth, press, TV -- let's make the United States on every Friday a sea of blue much like a homecoming football game in the bleachers. If every one of us who loves this country will share this with acquaintances, coworkers, friends, and family, it will not be long before the USA is covered in BLUE and it will let our troops know the once 'silent' majority is on their side more than ever, certainly more than the media lets on. The first thing a soldier says when asked 'What can we do to make things better for you?' is: 'We need your support and your prayers.' Let's get the word out and lead with class and dignity, by example, and wear something blue every Friday.

BY PATSY M. MILLER, PH.D. | AUGUST 10, 2011

Be aware of the Buzz

The defensive Africanized honeybee

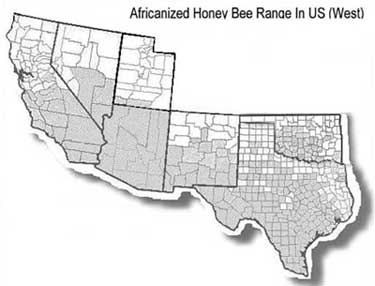

The African race of honeybee was introduced into Brazil from South Africa in 1956 to improve pollination and honey production of the various resident races of European honeybees. Unfortunately, 26 swarms headed by African queens accidentally escaped, spread through South America and steadily moved northward as they hybridized with resident bee populations. Africanized honeybees were first documented in Arizona when a colony was identified in Tucson in 1993. Today there are very few non-Africanized bees left in southern Arizona.

The African race of honeybee was introduced into Brazil from South Africa in 1956 to improve pollination and honey production of the various resident races of European honeybees. Unfortunately, 26 swarms headed by African queens accidentally escaped, spread through South America and steadily moved northward as they hybridized with resident bee populations. Africanized honeybees were first documented in Arizona when a colony was identified in Tucson in 1993. Today there are very few non-Africanized bees left in southern Arizona.

All honeybees look alike; only an expert can distinguish between European and Africanized races. What differentiates these new arrivals from the bees introduced by the European colonists is their defensive behavior. The sting of an Africanized bee is no worse than the sting of a European bee, but the habit of Africanized bees vigorously defending their hives after a slight jarring or vibration makes them more dangerous. Africanized bees react more quickly to disturbance, with more individuals inflicting stings, and pursue their victim over much longer distances than their European cousins. Research indicates that Africanized bees are more defensive where conditions are warmer, which is not comforting for us here in Arizona where summer temperatures are over 110º F for more days than we like to admit.

Bee colonies are formed when a new queen leaves the old hive with about half of the members of the colony. European bees usually swarm once a year during the late spring. Africanized honeybees swarm from four to six times per year, which facilitated their northward migration. Each swarm can contain 8,000 to 10,000 bees. The swarms that flew over the ridge where I was doing research in a tropical deciduous forest in Mexico were about 15 feet long and sounded like a freight train.

Individual “foraging” bees visiting flowers for nectar and transporting pollen are not overly defensive. Solitary bees will only sting if trapped, stepped on or threatened, but colonies of bees should be left alone. Dark colored clothing and strongly scented shampoo, soaps and perfumes may attract bees. Equipment that produces sound vibrations such as grass/weed whips or chainsaws may provoke a bee colony.

Bees nest in a wide variety of locations from saguaro cavities, rock crevices, irrigation valve boxes, to walls of homes. Bees require food, water and sheltered hive sites to survive. The best way to keep bees from establishing a colony on your property is to eliminate attractive hive sites, especially near living areas. Openings as small as a pencil eraser that lead to a cavity with space for a nest are ideal for colony establishment.

The best way to determine if you have a bee colony on your property is to observe bee flight. If three or four bees are observed flying in a direct path in and out of a small opening and if the returning bees have pollen on their legs, it is highly probable that there is an established colony behind the opening. Concentrated foraging for water from a swimming pool, fountain or pet watering container is another indication that there is a colony nearby.

The best way to determine if you have a bee colony on your property is to observe bee flight. If three or four bees are observed flying in a direct path in and out of a small opening and if the returning bees have pollen on their legs, it is highly probable that there is an established colony behind the opening. Concentrated foraging for water from a swimming pool, fountain or pet watering container is another indication that there is a colony nearby.

If you think there is a honeybee colony on your property, call a company licensed by the Arizona Structural Pest Control Commission (SPCC) listed under Bee Removal in the yellow pages to deal with it. Only companies with a SPCC license can purchase the chemicals required and eradicate an established bee colony. Once a property owner knows there is a colony on his property, he is responsible for its removal and has a liability if someone is injured by swarming bees. But most important, NEVER, NEVER disturb a colony in any way or try to remove it yourself.

In the unlikely event that you accidentally disturb a colony of Africanized bees, cover your head and eyes as much as possible and run. Do not attempt to swat the bees; they are attracted by agitated movement. Just get away fast. If possible find shelter in an automobile or building. After reaching a bee-free shelter, remove all stingers. When a bee stings and tries to fly away, the stinger is ripped from its abdomen. An individual bee cannot sting a second time. The bee dies, but you are left with the stinger and venom that continues to enter the wound for a short time. Do not pull the stinger out, because this will squeeze more venom into the wound. Scrape the stinger out with a fingernail or any straight-edged object. If you are stung and feel ill, you may be having an allergic reaction and should seek medical attention immediately, as you should if you are stung more than 15 times.

When horseback riding, be aware of possible sites under low hanging branches where bees might nest. Bees often sting horses inside the nose, possibly resulting in swelling and blockage of breathing. Dogs are more likely to disturb a bee’s nest if they are bounding through the brush than if they are walking on a leash. The number of stings that an animal can survive depends on its body weight. If an animal is stung numerous times, a trip to the vet is a good idea. Pets can also be allergic to bee stings.

Individual bees and colonies away from human habitation should be respected and left alone. Africanized bees can be dangerous, but even these cantankerous critters do us a great service. About one-third of our daily diet comes from crops pollinated by honeybees. We have to live with them because we cannot live without them.

The information in this article is based on the December 2003 talks by Dave Langston of the University of Arizona Agricultural Extension office and Scot Robinson of AAA Africanized Bee Removal Specialists, Inc., presented as part of the Desert Awareness Committee/Cave Creek Recreation Department lecture series, and from information supplied by the Arizona Cooperative Extension.

(Editor’s comment: According to speaker Dave Langston, and also Tom Martin, President of AAA Africanized Bee Removal Specialists, commercial honeybee operators regularly “re-queen” their hives to prevent Africanization. Regarding the feasibility of transplanting wild bee colonies, they explained that saving wild bees that have been Africanized is generally discouraged as it is more difficult and costly for beekeepers who prefer to not manage or re-queen highly defensive bees. Transplanting bees elsewhere in the wild is not feasible because the bees no doubt would move to a site of their own choosing. Even if moving them works, it would simply transfer the problem to someone else in the future. However, depending on safety issues, at a customer’s request transplanting can be given case by case consideration, for example with a swarm that has not yet been established.)