SEPTEMBER 22, 2010

SEPTEMBER 22, 2010

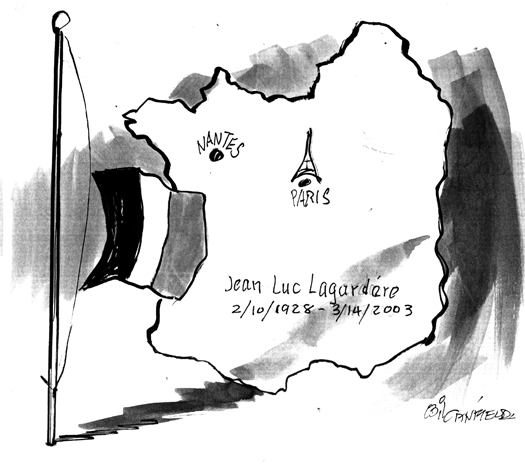

Jean Luc Lagardere et al

Among those I have encountered in a long business career, Jean Luc Lagardere was a standout.

I first met Lagardere when he strutted unannounced into my office. He was a natural marketer and a charming man. He introduced himself as the CEO of Matra, a French defense contractor. He had decided that Harris Corporation, for whom I worked, would be a good partner for a semiconductor joint venture in France.

His idea was daunting because I knew the powerhouse Intel was seeking to do the same thing with an able French partner.

Nonetheless, Lagardere’s plan looked more promising as we better understood his connections in the French government and other unusual powers he held.

Besides his friendship with the prime minster of France, he chaired Europe Number One, a TV station that was on German soil so it avoided French limitations of transmission power. As a consequence, Europe Number One transmitted to all of France, and that brought French politicians to kiss Lagardere’s ring.

He had an able staff. Pierre Foughere handled Matra investments in other American companies and negotiated contracts like this one. The other was Tony Degraff.

Degraff was the second in command of the French underground during WWII. When his boss was killed by the Germans, he became the leader. The British felt he was in mortal danger and smuggled him to Britain in a submarine.

After the war he became Lagardere’s business manager, and while negotiating a deal with Arabs, he became ill, completed the contract and went to his physician in France. He was told he had had a massive coronary.

When we met in early morning meetings, Rosemary, his secretary, laid out 33 multi-colored pills and he would toss them into his mouth while we prepared for the day over coffee.

Later, when I was CEO of a medical company I was told how aggressive European doctors were in the use of pharmaceuticals. Degraff was a good example, and in his case, it worked well.

Years later, when he died, there was a national day of mourning, honoring his life.

My concerns with Intel were alleviated when I talked to the two famous founders of Intel, Bob Noyce and Gordon Moore. They assured me there would be no hanky panky, and although competitors, they felt, as Americans, we should jointly cooperate. We did, they did, and the results were good for both companies.

The power held by Lagardere was demonstrated after our first visit with French Government officials.

Our French partners presented our joint venture plans. The officials refused to speak English so we were in the dark except for seeing negative body language. They turned to me for comment and I said, “I don’t speak your language, but the times all of you have said no, tells me your answer.”

We were despondent so Degraff took us to a foie gras restaurant that had a plank about 12 feet from the floor, with gallon jugs of French brandy much of which were up to 150 years old. We were told these treasures were hidden when France was occupied. The food and brandy were magnificent.

Next morning we explained our dilemma to Lagardere. He listened with no expression, dialed French Prime Minster Jacques Chirac and told him the government agency involved was stupid, and he wanted their decision changed.

Lagardere smiled and said, “Arrange another meeting, and you will like the outcome.” We confronted the sullen group the next day, and they grudgingly said yes, this time.

But the French government was willing to support the joint venture only if we placed it in Nante, France. Nante had once been a prominent builder of ships but the Japanese had taken their customers and the unemployment in Nante was grave.

We journeyed to Nante in a bus with Matra officials and drove near city hall. We were confronted by a large group of picketers, most carrying signs.

Uniformed officers with helmets and face masks escorted us to a below ground entrance. The elevator at the top floor opened into the mayor’s opulent office, which was decorated with museum quality paintings and sculptures.

We were seated at banquet table laden with hors d’ oeuvres after being greeted by the mayor with a firm handshake and hug.

After gracious thanks he said, “We had precautions to protect you but the people demonstrating want jobs, that is their message.” He went on to promise substantial job training and community support.

We located Matra-Harris Semiconductour at Nante and it was a moderate success. Matra later sold the business to a German firm.

Lagardere with many irons in the fire often flew in, usually on the Concorde, for our frequent meetings. He continued to try to get access to our crown jewels, our hugely profitable linear product line. Only our digital products were part of the joint venture.

Wikipedia best summarizes Legarderre’s fantastic life.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia:

Jean-Luc Lagardère (February 10, 1928 – March 14, 2003) was a major French businessman, CEO of the Lagardere Group, one of the largest French conglomerates.

Jean-Luc Lagardère was a Supelec engineer. He began his career in Dassault Aviation. CEO of Matra in the 1960s, he became famous with success in Formula One and Le Mans. He later built a large media and defense conglomerate that bears his name. He was a member of the Saint-Simon Foundation think-tank.

In 1981, with his friend Daniel Filipacchi, he purchased Hachette magazines, which included the French TV Guide (Tele 7 Jours), and the then-struggling Elle magazine. Elle was then launched in the U.S., followed by 25 foreign editions. Filipacchi and Lagardère then expanded Hachette Filipacchi Magazines in the U.S. with the purchase of Diamandis Communications Inc. (formerly CBS magazines), including Woman's Day, Car and Driver, Road and Track, Flying, Boating, and many others.

Lagardère was a prominent figure in French horse racing. In 1981, he purchased the renowned Haras d'Ouilly stud in Pont-d'Ouilly, Calvados that had been owned by François Dupré and raced under their famous colors of gray with a pink cap. At one time, his operation had as many as 220 horses. He won the French owners' championship in 1998 and between 1995 and 2001 was the leading breeder in France. His most important racing win came with Sagamix who won the 1998 Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe.

Upon its formation in 1995, Jean-Luc Lagardère served as the first president of France-Galop. On his death in 2003, the business was taken over by his son Arnaud who sold Haras d'Ouilly and its entire bloodstock in 2005 to the Aga Khan IV.

In 2002, the Group One Grand Critérium race for two-year-olds at Longchamp Racecourse was renamed in his honor.