Lew Jones was a man, who had his own club.

He lived before now, and now we learn, he has died.

People who met him in Old Cave Creek, thought he was a gruff, slit-eyed, opinionated and irascible bastard, to be avoided, after their clumsy attempts of insincere charm, could not work.

They were usually not from around here, and it easily showed. It offered a chance for us to smile at their failure.

The rest of us, of course, loved this man with the soft heart, the golden wit, the private smile he would share, like a horse whisperer with a favored steed. This meant you were in the club. He had observed you, thought you were different by comparison, and you had earned your way into his respect, because you were like many in early Cave Creek – you were authentic.

After that initiation, you were set, and he spoke to you in the currency of frontier people and cowboys — with stories, tall tales and shared sharp pieces of true and tragic gossip.

Cave Creek was not the city, not suburbia, but a sweetly hidden place by choice and by custom. Lots of heat and dust, this town was a place of few permanent residents, and those of us who lived here, knew each other by our vehicle, our spouse, our dog, and our children; in about that order. We each had an informal reputation. Lew knew them all.

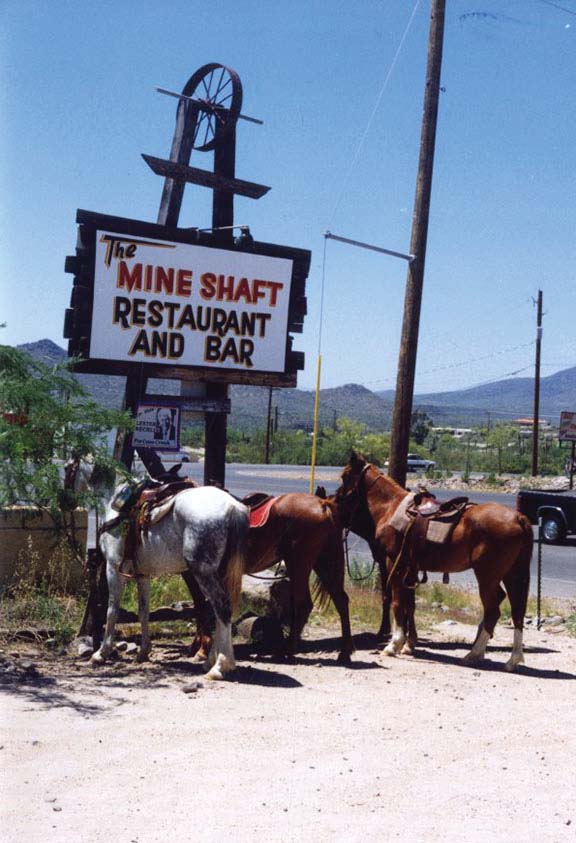

His restaurant which was more of an end-of-the paved road settlement, was called “The Mine Shaft,” and wife Tara

Jones was as gracious and welcoming as Lew was stoic and self-pleasingly judgmental.

The setting was sparse, the food was home made and the vibe was local, and intolerant of pretention.

When you stepped in, Tara never stopped working, wearily smiling, and coordinating hospitality with full food plates – Lew observed it all and visibly reigned, as only a man who is the master of all he sees, can be.

I loved when he would faintly smile, squint and then quietly say in your direction, “I cannot stand that sonofabitch.” It was ‘John Wayne-esque’ and the sound of a soaring hawk was rhetorically heard flying overhead.

It is funny the things you remember when someone dies. An era ends, admittedly significant only to yourself. Then you witness the reminding evidence of your own aging.

The memory of Al Capone’s door slam and swirling floor dust on a hot summer afternoon returns. You sit, turn inward, and watch a series of memory images flashing on our private brain theater screen. Time stops briefly and you are surprised of how much you remember, and the smiles it still evokes.

I liked the way Lew would start a conversational question with your name. “Well Tom, what do you think…”

Usually Lew listened more than he spoke, opined more than he listened, and included long pauses in a conversation appearing to look at some distant horizon and recording mental notes to himself. . This is what it mean to be in Lew’s club.

It was a time, at a place, in the personal company of a man who understood comradery and bestowed a special status that only comes from the fellowship of those who open a crack in their door, showing the private light, from a glimpse at their souls.

Life’s privilege and reward, given by another.

Way out West, where the sky is a little bluer and the handshake, a little firmer.

Somebody else said that, and it might have been Lew. I can’t really remember.

—Tom Augherton