In the U.S., we used to take economic growth for granted. From 1947 to 2004, it averaged an inflation-adjusted 3.45 percent growth a year, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

But that was then. Now growth is almost impossible to find. The economy has not grown above 4 percent since 2000 and not above 3 percent since 2005.

From 2006 to 2015, it has averaged just 1.41 percent a year, the worst economic performance since the Great Depression.

2016 is off to a rocky start, too, with the U.S. economy only growing at an annualized rate of 1 percent so far.

Now, speaking at the Detroit Economic Club on August 8, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump has promised the seemingly impossible: “We will make America grow again.”

But how does Trump say he would do that?

Trump’s plan calls for a pro-growth adjustment of policy on taxes, regulations and trade. That is lower and a fewer brackets simplification of taxes, the rollback of onerous regulations and a moratorium on new ones, and renegotiating trade and currency arrangements that have left American producers at a competitive disadvantage in the global economy.

It is an ambitious approach that targets excessive government-created costs on production — and emphasizes the value of work and taking care of one’s own family. Trump is offering jobs, not welfare, and argues we will be better off if we produce more as a nation.

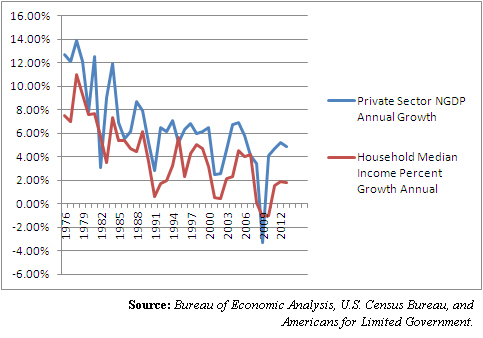

As far as growth, robust growth would help boost incomes, which have been flattened in the wake of the Great Recession. From 1976 to 2004, nominal household median income grew an average 4.64 percent a year, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. But from 2005 forward, it has only grown 1.95 percent a year.

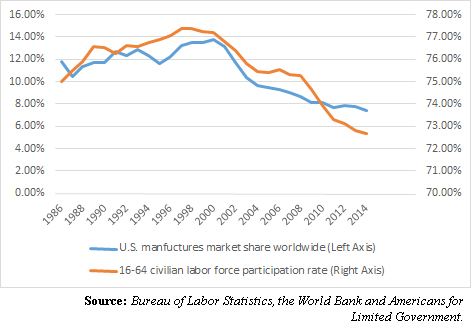

It would also create new jobs in the U.S., of which there is a pressing need. Since 2000, 7.3 million 16 to 64 year olds have simply dropped out of the labor force or not entered on a net basis, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. If they were included as a part of the labor force, the unemployment rate would be 9.3 percent today instead of 4.9 percent.

The drop in labor participation of 16 to 64 year olds from more than 77 percent to about 73 percent coincided with a definite drop in U.S. global market share of manufacturing. The U.S. market share of manufactures exports worldwide — that is, U.S. exported manufactures as a percent of worldwide exported manufactures — peaked in 1999 at 13.48 percent, and has been declining ever since, according to data compiled by the World Bank. In 2014, it was down to 7.45 percent.

Going back 30 years shows that as U.S. market share of manufacturing rose worldwide in the late 1980s and 1990s, so too did labor participation. And that once we were losing market share, labor participation followed closely behind.

To be fair, so too did consumer inflation drop, during a period of immense technological expansion. It became cheaper to buy the goods from overseas. But at a cost, since it is no longer cost-effective to make those goods in America, creating jobs. That is not advancement from horse and buggy to factory lines. We didn’t invent a new way of producing the goods, we used cheaper overseas labor. The jobs still exist, just not here.

So, based on the numbers, Trump has struck a chord. Economic growth, incomes and job creation have all suffered greatly in the past 15 years. Outsourcing production appears to be a major cause. What use are cheaper goods to those who have lost their jobs?

It explains why politically, Trump did so well in the Republican presidential primaries — by attracting millions of disaffected Republicans, Independents and Democrats who feel they have been left out of the benefits of the global economy. Those people begin to add up. In a republic, that means votes.

Now Trump’s challenge (and opportunity) in the general election is to turn that success into a new bipartisan majority that favors bringing outsourced jobs back to the U.S.

Time will tell if that message works — bringing together union household Democrats and Independents, and conservative Republicans is something that has arguably not been achieved since Ronald Reagan in 1984 — but the appeal is being made.

If Trump is not rewarded for that outreach in the general election, it may be a number of years before another Republican attempts to tackle these issues on the national stage — and those could be years that the U.S. simply cannot afford to lose. How could growth get any slower?

Donald Trump did not invent these challenges. Win or lose, the trade and immigration issues are not going away after 2016.

Besides, getting the economy moving again will be challenging no matter who wins the election. Another decade of slow to no growth, stagnant wages and abysmal job creation will haunt us for a generation — and nobody should want that or take it as a benign reading. There is a widening gap of opportunity between those who work — and those who are being left behind by the economy.

The lack growth is a real problem, and it is the true barometer by which a Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton administration will ultimately be judged: Did they help the economy, jobs and incomes start growing again?

As Americans for Limited Government President Rick Manning recently noted in a statement, “Growth is the answer that eludes us.”

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.