OWENSBORO, Ky. – Aug. 14 will mark the 80th anniversary of the last public execution in the United States.

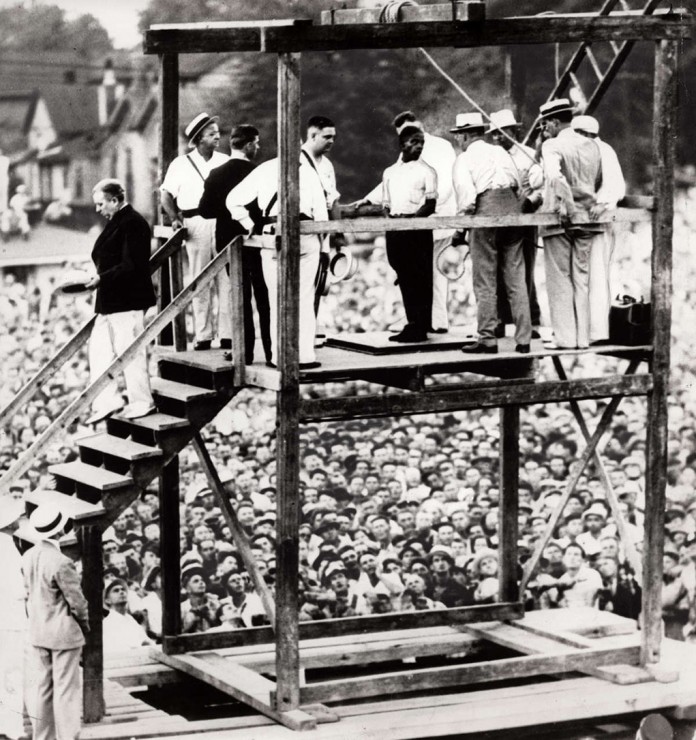

Rainey Bethea, a 27-year-old black man, was publicly hanged in Owensboro, Ky. on Aug. 14, 1936 for the rape of Lischia Edwards, a 70-year-old white woman.

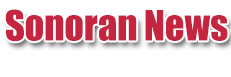

Not only did an estimated 20,000 people, including thousands from out of town, gather to watch the execution, the circumstances of the execution and the media circus that ensued embarrassed members of the Kentucky legislature enough to put an end to public executions in Kentucky and the United States.

Bethea, originally from Roanoke, Va., arrived in Owensboro in 1933 where he worked as a laborer earning $7 per week.

In 1935, he was charged with breach of the peace and fined $20.

Shortly thereafter, Bethea was caught stealing two purses valued at more than $25 each (equivalent to approximately $550 today) from a beauty shop and was convicted of grand larceny, a felony.

He was sentenced to one year in the Kentucky State Penitentiary and was paroled in December 1935.

Less than one month after his release, Bethea was arrested again for breaking and entering into a house.

The charge was later amended to drunk and disorderly. However, because he couldn’t pay the $100 fine (the equivalent of $1,738 today) he remained incarcerated until April 18, 1936.

On June 7, 1936, a drunken Bethea entered Edwards’ home and woke her when he climbed into her bedroom window.

After Bethea violently raped and choked Edwards, he searched her home for valuables and stole several rings.

Bethea, who removed his prison ring and inadvertently left it behind at Edward’s house, stashed the stolen jewelry in a nearby barn.

Edwards’ body was discovered late the same morning when concerned neighbors had not heard Edwards stirring about in her room and decided to make a welfare check.

It was the coroner who found Bethea’s celluloid prison ring, which several people told police they had seen Bethea wearing.

Because Bethea had a criminal record, police were able to employ new fingerprint technology to match Bethea’s prints to items he touched in Edwards’ bedroom.

After eluding police for several days Bethea was eventually spotted again on a river bank where he attempted to hop a barge.

When police questioned Bethea, he denied he was Bethea and told them his name was James Smith.

Bethea was arrested and later identified as Bethea by a scar on his head.

To avoid a lynch mob, a circuit court judge ordered the sheriff to transport Bethea to a county jail in Louisville.

It was during the transfer that Bethea confessed to raping Edwards and strangling her to death while lamenting about leaving his prison ring behind at the scene.

On June 12, 1936, Bethea made another confession as to where he stashed the stolen jewelry.

Under the statutes in force at the time, if the death penalty was given for murder and robbery, it had to be carried out by electrocution at the state penitentiary.

However, the punishment for rape could be carried out by public hanging in the county seat where the crime occurred, so prosecutors decided to only charge Bethea with rape.

After less than two hours, the grand jury indicted Bethea on the rape charge.

Bethea was never charged with murder or any other crime.

The night before his trial, Bethea decided he wanted to plead guilty, which he did the next day.

Prosecutors still had to present their case to jurors at trial because they would be the ones who decided Bethea’s sentence.

The case was infamous in Owensboro and surrounding areas but gained national attention because Daviess County Sheriff Florence Shoemaker Thompson, whose duty it was to hang Bethea, was a woman.

Thompson became sheriff in 1936 after her husband Everett Thompson, who was elected sheriff in 1933, died unexpectedly of pneumonia in April 1936.

After it became public knowledge Thompson would perform the hanging, letters to the sheriff poured in by the hundreds, including one from Arthur L. Hash, a former Louisville police officer, who offered to perform the hanging for free and only asked that his name not be released to the public.

Thompson promptly accepted his offer.

Chief Deputy U.S. Marshal for the District of Indiana also sent Thompson a letter informing her of a farmer from Illinois named G. Phil Hanna who had supervised numerous hangings across the country, although he never actually pulled the trigger that released the trapdoor.

Hanna apparently became interested in the art of hanging after witnessing the botched execution of Fred Behme in 1896 in McLeansboro, Ill, which resulted in Behme suffering.

Some people may recall the story about the hanging execution of convicted murderer Eva Dugan at the state prison in Florence, Ariz. in 1930, which resulted in her decapitation and influenced the state to replace hanging with lethal gas.

Hanna wanted to provide assistance with hangings to ensure a quick and painless death, although he didn’t always achieve that goal.

In 1920, during the hanging of James Johnson, the rope broke and Johnson was severely injured when he fell to the ground and Hanna had to carry Johnson back up the scaffold to carry out the execution.

Bethea was the 70th hanging execution Hanna supervised.

Gov. Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler signed Bethea’s execution warrant, setting the execution for sunrise on Aug. 14 in the courthouse yard.

Thompson requested a revised death warrant since the county had just planted new shrubs and flowers in the courthouse yard at great expense and didn’t want spectators trampling the gardens.

A second death warrant was subsequently issued, moving the execution to an empty lot near the county garage.

Bethea ate his last meal, consisting of fried chicken, pork chops, mashed potatoes, pickled cucumbers, cornbread, lemon pie and ice cream at 4 p.m. on Aug. 13.

Hanna visited Bethea in jail and instructed him he would need to stand on the X marked on the trapdoor.

On the morning of the hanging, Hash arrived drunk in a white suit and Panama hat. At that point, no one but he and Thompson knew he would be pulling the trigger.

Hanna placed the noose around Bethea’s neck, adjusted it and signaled Hash to pull the trigger.

The crowd watched in silence.

Hash was apparently too drunk to respond. Hanna yelled at Hash to “do it” to no avail.

Instead, a deputy leaned onto the trigger, springing the trapdoor and dropping Bethea eight feet, breaking his neck instantly.

Despite Bethea wanting his body sent to his sister in South Carolina, he was buried in a pauper’s grave at a cemetery in Owensboro.

Bill Shelton recalls in a YouTube video his parents taking him to the execution when he was young child.

Stating there were hawkers everywhere selling sandwiches and Coca Cola, Shelton said you would have thought you were at a picnic rather than an execution.

Newspapers from all over, after having spent considerable money to cover the first execution performed by a woman, left disappointed.

Several took liberties in reporting about the execution, some claimed Thompson fainted, while others claimed the crowd stormed the scaffolding for souvenirs.

The media circus surrounding the execution embarrassed members of the Kentucky General Assembly and prompted Sen. William R. Attkinsson, representing Louisville, to introduce Senate Bill 69 in 1938.

The bill, which passed both chambers and was signed into law by Gov. Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler on March 12, 1938, repealed the section of statute requiring death sentences for the crime of rape to be conducted by hanging in the county seat where the crime was committed.

The legislature only met biennially at the time, which is why it took until 1938 to introduce a bill.

Chandler subsequently expressed regret over signing the bill and stated, “Our streets are no longer safe.”

There were two other men hanged for rape in Kentucky after Bethea in 1937 but the trial court judges in both cases ordered the hangings to be conducted privately.