BY LINDA BENTLEY | jUNE 29, 2011

Injunction against California’s video game ban upheld

In Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Cinderella’s evil stepsisters’ eyes are pecked out by doves … Hansel and Gretel kill their captor by baking her in an oven

WASHINGTON – The U.S. Supreme Court issued another opinion on Monday in favor of the First Amendment, affirming the lower court’s permanent injunction against a California law restricting the sale or rental of violent video games to minors.

WASHINGTON – The U.S. Supreme Court issued another opinion on Monday in favor of the First Amendment, affirming the lower court’s permanent injunction against a California law restricting the sale or rental of violent video games to minors.

The U.S. District Court concluded the law violated the First Amendment, a view that was affirmed by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

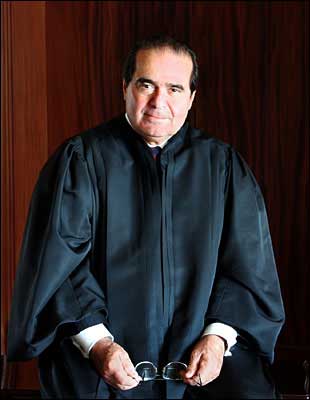

The opinion of the court was delivered by Justice Antonin Scalia (l), joined by justices Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

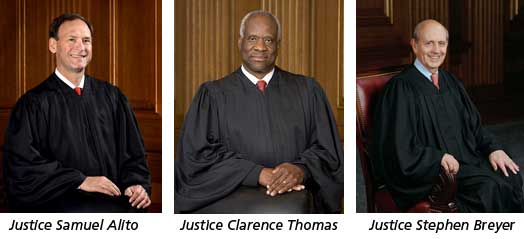

Justice Samuel Alito filed a concurring opinion, in which Chief Justice John Roberts joined, while justices Clarence Thomas and Stephen Breyer each filed dissenting opinions for quite different reasons.

California Assembly Bill 1179 prohibited the sale or rental of “violent video games” to minors and required their packaging to be labeled “18.” It covered games “in which the range of options available to a player includes killing, maiming, dismembering, or sexually assaulting an image of a human being, if those acts are depicted” in a manner that “[a] reasonable person, considering the game as a whole, would find appeals to a deviant or morbid interest of minors,” that is “patently offensive to prevailing standards in the community as to what is suitable for minors,” and that “causes the game, as a whole, to lack serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value for minors.”

Scalia stated, “The Free Speech Clause exists principally to protect discourse on public matters, but we have long recognized that it is difficult to distinguish politics from entertainment, and dangerous to try.”

Quoting from the 1948 case Winters v. New York, Scalia wrote, “Everyone is familiar with instances of propaganda through fiction. What is one man’s amusement, teaches another’s doctrine.”

He stated, “Under our Constitution, esthetic and moral judgments about art and literature … are for the individual to make, not for the government to decree, even with the mandate or approval of a majority,” and California was unable to show that the law’s restrictions met the alleged substantial need of parents who wish to restrict their children’s access to violent videos.

Because the U.S. Supreme Court has previously held violence is not considered obscene to youths nor is it speech subject to some other legitimate proscription, Scalia stated it cannot be suppressed “solely to protect the young from ideas or images that a legislative body may think is unsuitable for them.”

In a footnote, Scalia countered Thomas’ notion that persons under the age of 18 have no constitutional right to speak or be spoken to without their parents consent, stating Thomas cited no case, state or federal, supporting that view and there are none of which he is aware.

Stating California’s argument might fare better if there were a longstanding tradition of restricting children’s access to depictions of violence, Scalia said, “There is none.”

Noting children’s books “contain no shortage of gore,” using Grimm’s Fairy Tales as an example, Scalia stated, “As her just deserts for trying to poison Snow White, the wicked queen is made to dance in red hot slippers ‘till she fell dead on the floor, a sad example of envy and jealousy.’ Cinderella’s evil stepsisters have their eyes pecked out by doves. And, Hansel and Gretel (children!) kill their captor by baking her in an oven.”

Scalia pointed out high school reading lists are full of similar fare, citing Homer’s “Odyssey,” Dante’s “Inferno” and W. Golding’s “Lord of the Flies,” in which a schoolboy named “Piggy” is savagely murdered by other children while marooned on an island.

“This is not to say minors’ consumption of violent entertainment has never countered resistance,” wrote Scalia, noting in the 1800s there were dime novels depicting crime and books referred to as the “penny dreadful” (named for their price and content) were blamed by some for juvenile delinquency.

And, when motion pictures came along, Scalia stated they became the villains.

Scalia countered Alito’s accusation that the court was pronouncing playing violent video games “is not different in kind” from reading violent literature, by saying, “Well of course it is different in kind, but not in a way that causes provision and viewing of violent video games, unlike the provision and reading of books, not to be expressive activity and hence not to enjoy First Amendment protection.”

He continued, “Reading Dante is unquestionably more cultured and intellectually edifying than playing Mortal Kombat … Crudely violent video games, tawdry TV shows, and cheap novels and magazines are no less forms of speech than The Divine Comedy, and restrictions upon them must survive strict scrutiny.

Citing Winters, he wrote, “Even if we can see in them ‘nothing of any possible value to society . . . they are as much entitled to the protection of free speech as the best of literature.’”

In 1954, there was the crusade against comic books led by Dr. Frederic Wertham, a psychiatrist who testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee, stating, “[A]s long as the crime comic books industry exists in its present forms there are no secure homes.”

Wertham even objected to Superman comics, calling them “particularly injurious to the development of children.”

Alito found the violence in some of the games “astounding” with victims “dismembered, decapitated, disemboweled, set on fire, chopped into little pieces … blood gushes, splatters and pools.”

Scalia stated, “Justice Alito recounts all these disgusting video games in order to disgust us – but disgust is not a valid basis for restricting expression.”

Alito wrote, “The court’s opinion distorts the effect of the California law. I certainly agree with the Court that the government has no ‘free-floating power to restrict the ideas to which children may be exposed’ … but the California law does not exercise such a power. If parents want their child to have a violent video game, the California law does not interfere with that parental prerogative.”

Alito concluded, however, the law at issue failed to provide the clear notice the Constitution requires.

However, he stated, “I would not squelch legislative efforts to deal with what is perceived by some to be a significant and developing social problem.”

Thomas, in his dissent, stated, “In the typical case, the only speech affected is speech that bypasses a minor’s parent or guardian … ‘The freedom of speech,’ as originally understood, does not include a right to speak to minors without going through the minors’ parents or guardians. Therefore, I cannot agree that the statute at issue is facially unconstitutional under the First Amendment.”

Breyer stated, “This case is ultimately less about censorship than it is about education. Our Constitution cannot succeed in securing the liberties it seeks to protect unless we can raise future generations committed cooperatively to making our system of government work.

Education, however, is about choices. Sometimes, children need to learn by making choices for themselves. Other times, choices are made for children—by their parents, by their teachers, and by the people acting democratically through their governments. In my view, the First Amendment does not disable government from helping parents make such a choice here … which they more than reasonably fear pose only the risk of harm to those children.”