WASHINGTON – The U.S. Constitution provides that federal judges shall hold their offices during “good behavior,” which means they cannot be dismissed but can be impeached for misconduct.

There is nothing in the Constitution stating such judicial appointments are for life.

The Judicial Conference of the United States, originally enacted by Congress in 1922 as the Conference of Senior Circuit Judges, was created after more than a decade of public debate as a means of reforming judicial administration and to address the backlog of federal court cases.

It is headed by the Chief Justice of the United States and consists of the Chief Justice, the chief judge of each court of appeals federal regional circuit, a district court judge from various federal jurisdictions and the chief judge of the United States Court of International Trade.

After leaving the White House in 1913, President William Howard Taft, who was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1921, led a public campaign for judicial reform.

His proposal included the appointment of at large judges, or what he called a “flying squadron” that could be temporarily assigned to congested courts and the Conference of Senior Judges would serve to assess the caseload of lower courts and assign the at-large judges to courts requiring assistance.

Taft’s proposal to create a more efficient judiciary was also intended to thwart Sen. George W. Norris’s crusade to end life tenure on the federal bench.

Norris was a leader of progressive and liberal causes during his five terms in Congress despite being registered as a Republican during his first four terms. He served his final term as an Independent and was defeated in his bid for reelection in 1941. Norris died two years later at the age of 83.

After Taft became Chief Justice, the increased caseload from World War I and the enforcement of Prohibition garnered broad support for judiciary reforms.

When Congress passed the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act of 1980, it provided citizens with a means to file a complaint against a federal judge that they have reason to believe has committed misconduct or has a disability that interferes with his or her judicial duties.

Misconduct is defined in the Act as “conduct prejudicial to the effective and expeditious administration of the business of the courts,” while disability is considered a temporary or permanent condition, either mental or physical, that makes the judge “unable to discharge all the duties” of the court.

Some examples of misconduct include using the judge’s office to obtain special treatment for family or friends; accepting bribes, gifts or other personal favors related to the judicial office; having improper (ex-parte) discussions with parties or counsel for one side in a case; treating those before the court in a demonstrably egregious and hostile manner; engaging in partisan political activity and more.

Complaints may also address actions taken by a judge outside his or her official role as a judge if “the conduct might have a prejudicial effect on the administration of the business of the courts, including a substantial and widespread lowering of public confidence in the courts among reasonable people.”

However, grounds for misconduct or disability complaints do not include an unfavorable judicial decision, which must be challenged through the judicial process.

While the rules for filing complaints are spelled out on http://www.uscourts.gov/judges-judgeships/judicial-conduct-disability/faqs-filing-judicial-conduct-or-disability-complaint, judges are still reviewing their own behavior.

For example, an April 12, 2010 Memorandum of Decision was filed in response to a complaint against District Judge Manuel L. Real from the Central District of California alleging he committed misconduct by failing in a number of instances to provide reasons for his judicial rulings.

In one of the cases before Real, the complaint alleged he committed misconduct by disobeying an appellate mandate.

A previous complaint against Real in 2007 resulted in a finding of misconduct and a private reprimand.

While the order notes the first petition argued “misconduct had been rightly found (albeit deficiently sanctioned),” the Committee on Judicial Conduct and Disability concluded a failure by a judge to state reasons for the judge’s judicial decisions could be misconduct only if the failure was wilful – a finding not evident from the Council’s order.

A finding of wilfulness, according to the Committee, would require “clear and convincing evidence of a judge’s arbitrary and intentional departure from prevailing law based on his or her disagreement with, or willful indifference to, that law.”

The special committee found no single instance in which Real’s failure to state reasons was willful within the meaning of the Committee’s instructions.

It also found neither (1) a “virtually habitual” failure to give reasons nor (2) a “substantial” number of cases in which such failure occurred after a remand that had, in the same or similar case, directed Real to give reasons.

Adopting the special committee’s findings and report, the Judicial Council dismissed the complaints, although it expressed concern about the conduct in question and stated it was “troubled by the District Judge’s failure in many cases to give reasons for his rulings where the law requires that reasons be given, and by the District Judge’s obduracy in implementing many directives from the appellate court.”

The Council concluded, despite finding Real’s conduct not to be “virtually habitual” or found in a “substantial number” of similar cases, it in no way lessened the importance of and the need to give reasons for a decision when required by law.

Although the Council was unable to find willfulness in any of the instances, it stated if Real were to continue such conduct, a future Council would no longer need to seek a pattern and the Memorandum of Decision placed Real on notice that a judge must state reasons for any judicial decision for which the law requires the giving of reasons.

A footnote stated, “Judge Real demonstrated that he knew of this concern when, in a Feb. 8, 2007 letter to the special committee’s presiding officer, he pledged to use his best efforts to state reasons when required to do so … No such efforts were evident, however, in an order he issued several months later, in which he refused to certify a settlement class. That order, the Ninth Circuit found, offered ‘almost no analysis’ and thus was unentitled to ‘the traditional deference given to class certification decisions.’ The court ordered the case reassigned on remand to a different judge.”

Nonetheless, the Memorandum and Decision denying the petition for review was signed by the seven-member committee made up of three Reagan appointees, two Bush appointees, one Ford appointee and one Carter appointee.

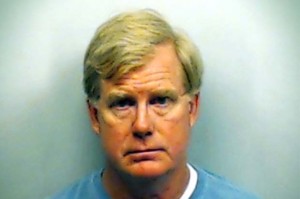

A more recent Memorandum of Decision was filed on July 8, 2016 regarding a complaint against U.S. District Judge Walter S. Smith, Jr. of the Western District of Texas alleging Smith made inappropriate unwanted physical and non-physical sexual advances against a court employee in 1998.

On Dec. 3, 2015, the Judicial Council confirmed the misconduct, reprimanded and suspended Smith from being assigned any new cases for one year and ordered him to undergo sensitivity training.

The complainant called Smith’s punishment “far too lenient” and urged the Judicial Conduct and Disability Committee to recommend impeachment.

The complainant also provided names of witnesses to other alleged incidents where Smith sexually harassed women in the courthouse, believing the assault of the one court employee was not an isolated incident.

The Committee returned the matter to the Circuit Judicial Council with directions to undertake additional investigation and make additional findings where appropriate and reconsider the appropriate sanction if there were additional findings.

The Committee also noted Smith allowed “false factual assertions in response to the complaint” and requested additional findings and recommendations as to the manner in which Smith’s conduct adversely impacted or interfered with the inquiry, if at all.

Smith served as a judge on State District Court in Waco, Texas from 1980 to 1983, became a U.S. Magistrate Judge for the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas in 1983 and was appointed a judge in September 1984 by President Ronald Reagan to fill a newly created seat.

He served as chief judge from 2003-2010 and retired in September 2016, most likely due to the additional investigation.

A footnote in Smith’s Memorandum of Decision refers to two instances in which the Judicial Conference of the United States issued a Certificate of Consideration of Impeachment of former U.S. District Judge Mark E. Fuller (Sept. 9, 2015) and U.S. District Judge Samuel B. Kent (June 9, 2009).

Fuller was accused of physically abusing his wife both before and after they married, including an assault that took place on August 9, 2014 in the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in downtown Atlanta, Ga. and made repeated statements under oath that were false.

Kent pled guilty in court to a single felony count of obstruction of justice.

Kent stipulated, as the basis for his guilty plea, that in August 2003 and March 2007, he engaged in non-consensual sexual contact with a person (Person A) without her permission; from 2004 through at least 2005, he engaged in non-consensual sexual contact with a person (Person B) without her permission; and in connection with a judicial misconduct complaint against him, he testified falsely before a Fifth Circuit special investigative committee regarding his unwanted, non-consensual sexual contact with Person B, by understating the extent of that contact and by falsely stating that it had ended after Person B told him it was unwelcome.

He was sentenced to 33 months imprisonment with an order to surrender on June 15, 2009.

Kent’s subsequent request to be certified for disability retirement was denied.

The Chief Justice of the United States stated “Kent’s conduct and felony conviction, as described above, have brought disrepute to the Judiciary.”

So, impeachment appears to be a large hurdle to conquer when it comes to federal judges, although it would appear the judges that halted President Trump’s temporary travel ban from six Muslim-majority countries that are known to harbor terrorists could fall under a finding of willfulness, whereas there is “clear and convincing evidence of a judge’s arbitrary and intentional departure from prevailing law based on his or her disagreement with, or willful indifference to, that law.”